Dieting to lose weight (even under the guise of “lifestyle changes”) is so normalized in our culture that it indeed feels normal. And if it’s “normal” it must be OK…right? Let me break this to you gently — not only can dieting lead to disordered eating, but in many cases, dieting IS disordered eating.

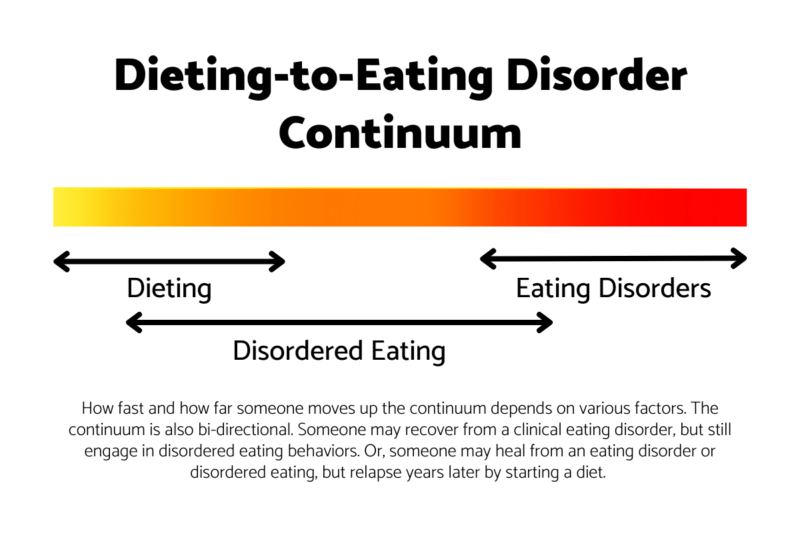

Many things exist on a spectrum, or continuum, and dieting, disordered eating, and clinical eating disorders are a few of those things. Exhibit A:

Dieting…or disordered eating?

A 2008 survey by University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Center for Excellence for Eating Disorders, in partnership with SELF Magazine, found that 65 percent of 4,023 American women between the ages of 25 and 45 who answered detailed questions about their eating habits reported having disordered eating behaviors. (An additional 10 percent of reported symptoms consistent with eating disorders such as anorexia, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder.)

Among the results were these findings:

- 53 percent of dieters were already at a healthy weight but were still trying to lose weight.

- 39 percent of women said concerns about what they eat or weigh interfere with their happiness.

- 37 percent regularly skipped meals to try to lose weight.

- 27 percent would be “extremely upset” if they gained just five pounds.

- 26 percent cut out entire food groups.

- 16 percent had dieted on 1,000 calories a day or fewer.

How many of these six behaviors are typical for people who are dieting? If you said most or all of them, then you get a gold star.

Now, how many of them are examples of disordered eating behaviors? If you said all of them, you get a whole sheet of gold stars.

Yes, eating habits that most women think are normal – such as shunning carbohydrates, skipping meals and engaging in diets that have a long list of food rules – may actually be symptoms of disordered eating.

And if you think that the situation has improved overall since 2008, please think again. Sure, more people are cluing into more health-supportive, life-affirming practices like Intuitive Eating, and are doing work to heal poor body image and become more embodied, but this is a slow train we’re talking about.

If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck…

The UNC authors defined disordered eating as “endorsing unhealthy or maladaptive eating behaviors, such as restricting, binging, purging, or use of other compensatory behaviors, without meeting criteria for an eating disorder.”

I think what surprises many people about that definition is the word “restricting.” It’s easy to see why restricting food intake — whether calories, macros, points or specific food groups — is “unhealthy or maladaptive” in the context of a restrictive clinical eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa.

It’s not so easy to see why restricting food is unhealthy or maladaptive in the context of trying to lose weight through dieting or “lifestyle changes,” especially when health is one of your reasons.

But trying to create a “calorie deficit” by eating fewer calories than your body needs and/or exercising with the primary goal of “burning calories” (as opposed to exercising because you like the activity, because it makes you strong, because it works your heart and lungs, etc.) is starvation.

Your body does not know the difference between not getting enough food because you’re experiencing poverty or a famine and not getting enough food because you are intentionally trying to shrink your body.

I know. That’s not a message you typically get when you are encouraged by friends, family, partners, the media or your doctor to “eat less and move more.”

Moving up the continuum

If you’ve never manipulated your eating and exercise to try to shrink or reshape your body, the first time you do can have a certain innocence to it. Maybe you…

…just want to “get healthy.”

…gained a bit of weight because you went through a period of time when you were eating on the fly and didn’t have time to do your usual physical activity.

…want to look better in your wedding dress or in a bikini.

…had your first child and want to regain your pre-pregnancy body.

…are dating again after ending a long relationship.

…are approaching menopause and noticed some “thickening” around your middle.

Most people probably see their first diet as self-care, or a little improvement project. They see results, and this is encouraging. They feel successful, and maybe feel better about how their bodies look. But these feelings are fickle, and dependent on maintaining these changes.

Given that about 95 percent of people who intentionally lose weight regain it within a few years, if not sooner, this sets the stage for chronic dieting, feelings of failure with each round of weigh regain, and increased food and body obsession.

Hello, disordered eating. Turns out dieting is not an innocent behavior.

Many people who struggle with disordered eating behaviors and mindset don’t fully realize how it can harm their mental and physical health. This lack of awareness can amplify those harms, which include not just increased risk of eating disorders, but also bone loss, gastrointestinal disturbances, electrolyte and fluid imbalances, low heart rate and blood pressure, increased anxiety, depression and social isolation.

(Note: Some people zoom up the continuum with their first diet. One thing leads to another, and they quickly develop an eating disorder.)

Setting the stage for shame

Women try to change their body size or shape for various reasons. I mentioned health and aesthetic/appearance, but a deeper reason is striving to be worthy.

Whether it’s a woman wanting to…

…be physically appealing to her partner or potential partners

…look professional and “put together”

…hold on to her identity as someone who’s thin and fit (i.e., hold on to thin privilege)

…feel listened to and not dismissed at the doctor’s office

…have a body that “fits in” with her family or peer group

…avoid the weight-based stigma that’s she’s observed other people be subjected to

…it’s very easy to come to believe that her self-worth is contingent on her body looking and/or functioning the “right” way. This taps into society’s thin ideal, as well as ableism and racism.

A woman who has mobility issues may feel like she already has one strike against her, so she can’t possibly allow herself to be in a larger body. Similarly, Black or brown women may feel the inescapable weight of oppression in ways large or small because of their skin color, so try to escape additional weight-based oppression through food restriction and/or excessive exercise. (For more on this last part, I highly recommend Jessica Wilson’s book, “It’s Always Been Ours: Rewriting the Story of Black Women’s Bodies,” which I reviewed for The Seattle Times.)

When you feel that you are not worthy, not only can that dredge up a lot of shame, but you may not feel safe.

We humans have a need to belong, a need that stretches back to our cave people ancestors, who risked being on their own to hunt and gather food and fend off sabertooth tigers if they weren’t worthy of belonging to the group. That’s safety in a literal sense.

Moving towards healing

I can say that your worth is not in your body. It’s not in how your body moves. It’s not in the shape or size of your body. It’s not in your skin color. It’s not in how much cellulite you have or how firm your skin is. It’s not in how many wrinkles and lines you have. You are uniquely you, and you inherently have worth.

But…I know that if you are already in a place where you DO believe your worth is based on those things, that my words may sound like a nice idea…maybe for other people but not for you.

If you DO feel like your worth is in your body, and you’re now suspecting (or maybe already suspected) that your eating and exercise habits are disordered, healing needs to happen on two fronts:

- Moving away from your habitual dieting/disordered eating behaviors, which involves unlearning diet culture’s message and relearning what an authentic, intuitive relationship with food looks like.

- Making peace with your body (whether that looks like body respect, body neutrality or body liberation) and excavating why you came to believe that your body isn’t good enough, and therefore YOU aren’t good enough.

Both parts are important, because giving up on restrictive eating and probably joyless exercise is hard to do unless you also do the body peace work. It’s not necessary to work on both parts simultaneously, but it can be helpful. I have many clients who started down the intuitive eating path on their own but then hit a roadblock because they hadn’t also addressed their body dissatisfaction and underlying beliefs.

This is where working with a registered dietitian nutritionist and/or a therapist who is weight-inclusive (and ideally trauma-informed) with training in body image helps.

A few books to get you started

- “Intuitive Eating: A Revolutionary Anti-Diet Approach” by Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch

- “More Than A Body: Your Body Is an Instrument, Not an Ornament,” by Lindsay and Lexie Kite

- “The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love” by Sonya Renee Taylor

- “The Body Liberation Project: How Understanding Racism and Diet Culture Helps Cultivate Joy and Build Collective Freedom,” by Chrissy King

- “The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook: A Proven Way to Accept Yourself, Build Strength, and Thrive” by Kristen Neff and Christopher Germer

- “Reclaiming Body Trust: A Path to Healing and Liberation” by Hilary Kinavey and Dana Sturtevant

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Disclaimer: All information provided here is of a general nature and is furnished only for educational purposes. This information is not to be taken as medical or other health advice pertaining to an individual’s specific health or medical condition. You agree that the use of this information is at your own risk.

Hi, I’m Carrie Dennett, MPH, RDN, a weight-inclusive registered dietitian, nutrition therapist and body image counselor. I offer compassionate, individualized care for adults of all ages, shapes, sizes and genders who want to break free from eating disorders, disordered eating or chronic dieting. If you need to learn how to manage IBS symptoms with food, or improve your nutrition and lifestyle habits to help manage a current health concern or simply support your overall health and well-being, I help people with that, too.

Need 1-on-1 help for your nutrition, eating, or body image concerns? Schedule a free 20-minute Discovery Call to talk about how I can help you and explore if we’re a good fit! I’m in-network with Regence BCBS, FirstChoice Health and Providence Health Plan, and can bill Blue Cross and/or Blue Shield insurances in many states. If I don’t take your insurance, I can help you seek reimbursement on your own. To learn more, explore my insurance and services areas page.

Print This Post

Print This Post