Update 3/12/22: While I stand by this post, I do not currently support Lindo Bacon in light of recent accounts of a long-term pattern of bad behavior directed towards fat and/or BIPOC individuals. Basically, their private actions are very different than their public words. Until Lindo takes appropriate accountability for their actions, and makes repairs, I will not give them my support.

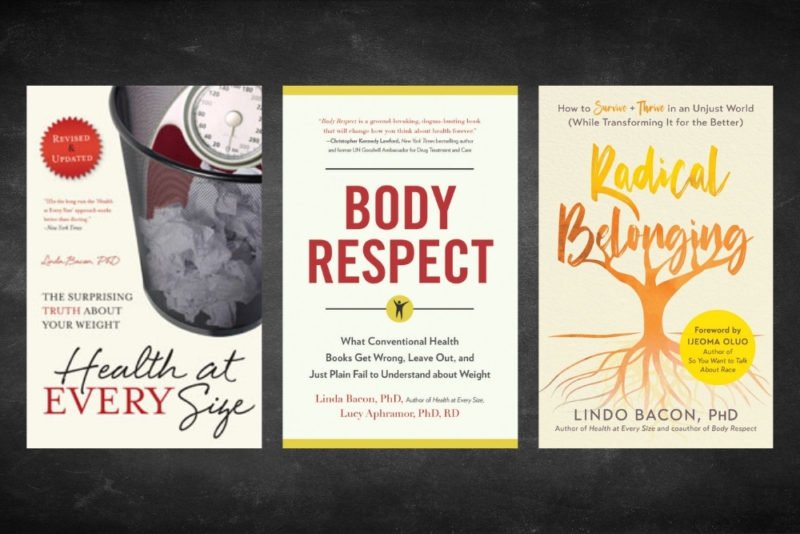

In my column last week for The Seattle Times, I reviewed the new book from Lindo Bacon, “Radical Belonging.” As is often the case when I interview book authors, there’s a lot of material that gets left on the “cutting room floor” because I run out my allotted words. This also happened when I interviewed Bacon (who then went by Linda)* and their co-author Lucy Aphramor in 2014 about their then-new book “Body Respect: What Conventional Health Books Get Wrong, Leave Out, and Just Plain Fail to Understand About Weight.”

*Briefly, Bacon now publicly identifies as genderqueer, neither male nor female, and goes by Lindo instead of Linda, the name their first two books were written under. Bacon also uses the pronouns they/them/theirs, and generously shares their story in the book.

I remember clearly when I first read Bacon’s first book, “Health at Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight,” which came out in 2010. I was a few months into grad school at the University of Washington, where I was working on my master’s degree in nutrition. My whole reason for returning to school and studying nutrition so I could become a registered dietitian (my first career was journalism) was so I could help people lose weight. I was riding high on my latest “successful” diet attempt (which was more like a full-on, obsessive, all-encompassing body project), and I was sure I had cracked the code.

Hahahahahahahahahahahaha!

The evolution from HAES to belonging

Anyway, I read “Health at Every Size” and was blown away. I thought it was absolutely fantastic that people did not have to lose weight in order to improve their health. It started to make me rethink how I wanted to help other people but did nothing to make me rethink how I wanted to treat myself. (I had a similar experience when I read “Intuitive Eating” around that time, “That’s great for other people, but not for me.”) No, I was not very kind to myself back then, perfectionist that I was (and still am, but I learned how to temper that trait with self-compassion).

(If you want to hear more about my personal and professional extraction from diet culture, give episode #194 of the Food Psych podcast, on which I guested, a listen.)

Well, I’m not the only one that evolved. Bacon acknowledges that when they wrote “Health at Every Size,” they were coming from a place of unexamined privilege. In other words, while they laid out the science showing that health was not as dependent on a lower body weight as we are led to believe, they still promoted the idea that health is our personal responsibility, by way of “healthy habits.”

When Bacon came to realize that the ability to make “lifestyle changes” is a class privilege (in other words, it’s easier when you have higher socioeconomic status and are not a member of a marginalized group), I know they wanted to take back some of the personal responsibility stuff in that first book (I’ve heard them speak about this in a very heartfelt way). While many people have been helped by that book, which Bacon appreciates, with “Radical Belonging” they offer a fuller picture of what it takes for our society to be healthier, both physically and psychologically.

Reading that resonates

I had a weird reaction to “Radical Belonging” as I started to read it. Even though the book is very readable, and I could easily have devoured it in a few days, I didn’t want to. I would find myself reading a few, or sometimes several, pages and the just want to set the book aside so I could reflect on and fully digest what I just read.

It wasn’t as if what Bacon was writing about was wholly unfamiliar to me. I’ve been doing my own self-study on trauma, privilege, social justice and embodiment for a few years now. Plus, I was well-versed in the idea of social determinants of health thanks to studying nutrition under the umbrella of UW’s School of Public Health.

I remember being almost giddy as I read Bacon’s 8-page description of the biology of stress in Chapter 2 (“This Is Your Brain on Stress”). It brought together bits and pieces I already knew and fleshed them out gloriously (yes, I was totally geeking out). And when I read these paragraphs on page 54, I immediately wanted to share them with several of my clients who had endured emotional neglect and uncertainty in childhood, despite having their material needs met:

“The invisible nature of some traumas can leave us confused. To an outside observer, an emotionally deprived child might appear fine, since their basic physical needs such as clothing and schooling are fulfilled. The lack of external recognition makes the invisible scars more damaging. The child feels unloved and unworthy, all the while hearing from society that they are well taken care of. This disconnect can create confusion, guilt and shame.

“Unfortunately, too many traumatic encounters go unrecognized by typical diagnostic criteria. This is unfortunate because people may then feel ashamed that what they experienced isn’t really trauma and thus is unworthy of attention.”

Outtakes on vulnerability and connection

It’s a fundamental human need to be seen, and to see ourselves reflected in the world. It’s what helps feel connected to humanity, to feel that we belong. But many of our fellow humans are NOT truly seen, whether it’s because they are part of a marginalized group, or because they are seen only for what they present on the surface. And that’s a big problem.

“There are plenty of people who on the one hand project to the world complete confidence and they seem so together, but what might be inside is someone who’s very lonely and disconnected,” Bacon said in our interview. “If you don’t see that fragility in them, if we only see them for the strength they’re projecting or the confidence they have…it just keeps reinforcing that that person is just valued for their achievements, or whatever they’ve been told gives them value in the world, and that person will continue to feel lonely, and you might feel jealous or inadequate because you don’t feel so together and you wonder why everyone else is.”

Bacon said what’s missing is that both people in this scenario don’t feel particularly good about themselves. “If you don’t show people all of your vulnerability you don’t get accepted for who you are — just for that image you’ve managed to project. Being valued for experience doesn’t cut the loneliness. It doesn’t support value for what someone is.”

Here’s some more food for thought from Bacon: “The people in front of us are not the people we’ve been taught to see them as. We’ve been taught to see them as stereotypes…we don’t know what’s underneath that. How can we make the world safe enough that they can reveal their true selves?”

Outtakes on body liberation

Bacon offers a robust and nuanced discussion of the idea of body liberation (including embodiment) in their book, and I was excited to ask them more about this, since I’ve been moving away from the idea of “body image” and towards body acceptance/respect/liberation and embodiment for a while. But alas, it didn’t make it into my article. Everything Lindo said relates to various aspects of the body, whether it be size, shape, skin color, visible disabilities, gender presentation, etc.

- “In body liberation, what we’re saying, let’s not reduce people into whatever we are reading onto their body, but let themselves live the best life they can based on the body they have.”

- “When you see somebody, you are able to see them beyond your stereotypical ideas of who they are based on their body.”

- “One of the problems with the whole body love generation is that we’re supposed to love the body we have, but that doesn’t address that our body marks us in the world. Our body will always be a symbol of things that mark us, that either give us resources and advantage, or take them away.”

- Related to that: “Embracing ourselves in any body that we have and recognizing that that body exists in the social context, and we also have to allow for that, too..” (In other words, if you’re in a body that doesn’t uphold cultural norms, and you are at peace with that, you still exist in a world that tells you you shouldn’t be at peace with that.)

- “There’s a problem in the culture, not in your body — but you’re experiencing that disconnect.”

A quick look back

When I interviewed Bacon and Lucy Aphramor in 2014, we had an amazing chat in a Phinney Ridge coffee shop. I had so much unused material that I spun it into four blog posts:

- HAES and society

- HAES and the healthcare system

- Health obsession and “body projects”

- Dieting, eating disorders and embracing HAES

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Disclaimer: All information provided here is of a general nature and is furnished only for educational purposes. This information is not to be taken as medical or other health advice pertaining to an individual’s specific health or medical condition. You agree that the use of this information is at your own risk.

Hi, I’m Carrie Dennett, MPH, RDN, a weight-inclusive registered dietitian, nutrition therapist and body image counselor. I offer compassionate, individualized care for adults of all ages, shapes, sizes and genders who want to break free from eating disorders, disordered eating or chronic dieting. If you need to learn how to manage IBS symptoms with food, or improve your nutrition and lifestyle habits to help manage a current health concern or simply support your overall health and well-being, I help people with that, too.

Need 1-on-1 help for your nutrition, eating, or body image concerns? Schedule a free 20-minute Discovery Call to talk about how I can help you and explore if we’re a good fit! I’m in-network with Regence BCBS, FirstChoice Health and Providence Health Plan, and can bill Blue Cross and/or Blue Shield insurances in many states. If I don’t take your insurance, I can help you seek reimbursement on your own. To learn more, explore my insurance and services areas page.