Life has been rough for many, many months now, but how this lingering pandemic life is affecting us doesn’t only have to do with its direct effects on our health or livelihoods — it has to do with how resilient we are. Like it or not, some people are more emotionally resilient than others. Observing my friends, family and clients, I’ve seen some people weather the storms of 2020 and 2021 in stride, while others are really struggling, ping-ponging between anger, denial and frustration that life as we use to know it has yet to fully return. Unfortunately, this only increases suffering.

When we’re suffering, it’s harder to make decisions and take actions that contribute to our long term health and happiness. We’re more likely to engage in impulsive, less-helpful coping mechanisms such as emotional eating. (I say “less-healthy,” because if food is the only way you have to cope, and you need help coping, then thank goodness you have food in that moment. But ultimately, it’s better to have many healthy ways to cope, so food isn’t your only go-to.)

Ironically, if you’re restricting your food — whether cutting calories or putting certain foods or food groups “off limits” — this lowers your resilience and increases the chance that you turn to food whenever you reach a breaking point. I see this all the time in my clients who have been restricting. When they start to listen to what their bodies need, and start to make peace with formerly “forbidden” foods, they not only have more mental space, but they find they are more resilient to life’s stresses.

The bottom line is that resilience isn’t just a “in our heads” thing: being more resilient can have positive effects on physical health and well-being, and caring for our physical health and well-being can help us be more resilient.

Retraining our brains: overcoming negativity bias

If you tend to be a glass-half-empty person, you’re not alone. From an evolutionary perspective, having a “negativity bias” helped to keep us safe (especially from sabertooth tigers). Being attuned to danger (which is definitely negative), helped our ancestors survive long enough to pass on their genes to the next generation. So we really come by our negativity biases honestly!

While we all have an innate negativity bias, some people are naturally more resilient than others, better able to:

- Stay calm when life isn’t

- Respond flexibly to changing conditions and situations

- See all the options, clearly

- Take wise action rather than staying frozen or behaving impulsively

- Persevere even when the situation is discouraging

Evolution aside, our capacity for resilience is largely shaped in childhood. If we felt safe, accepted and understood, we likely grew up to be more resilient. But the good news is that we can learn to be more resilient, to develop those traits (and recover them if trauma stole them from us along the way), even as fully formed adults. That’s because the neural networks that determine how we cope and behave when life hits bumps in the road can be reshaped by our choices and actions.

Self-compassion is a powerful tool for shifting to a glass-is-half-full mentality. Not only does this help you feel better, but it helps you function better–and to become more resilient.

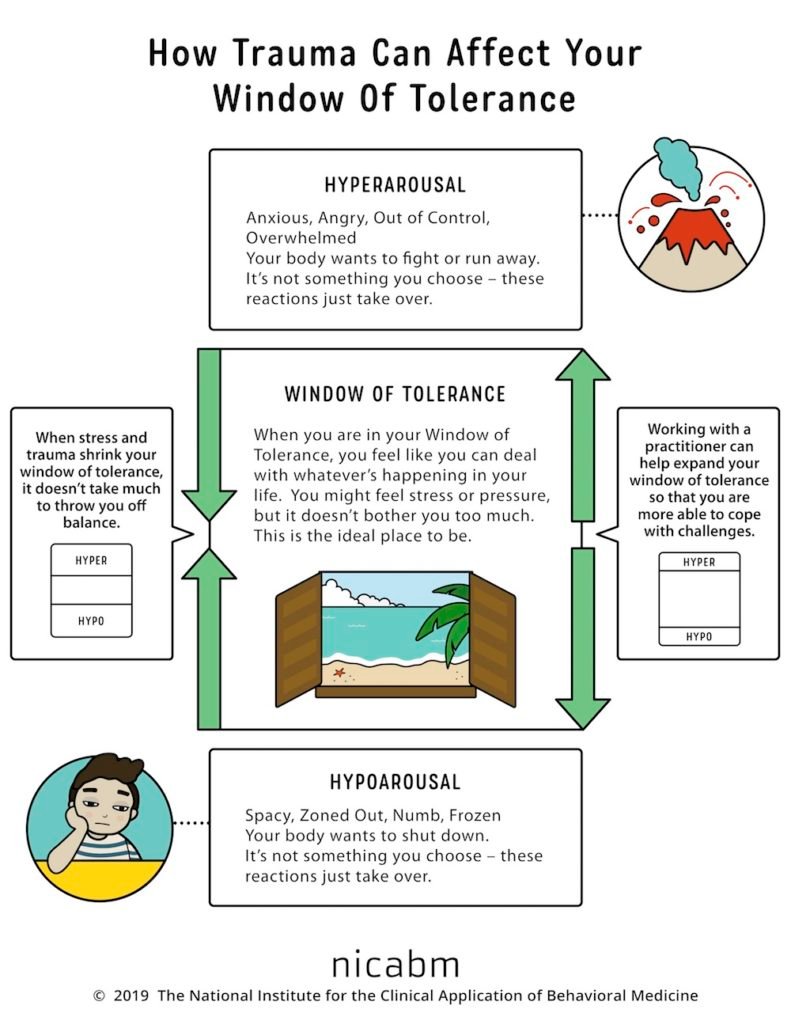

Window of tolerance

Before I get to self-compassion, I want to introduce the concept of the “window of tolerance,” because this relates to resilience. When you have a wide window of tolerance, you are able to respond effectively to a wide range of stress intensity. When you have a narrow window of tolerance, it doesn’t take much stress for you to become anxious and out of control (hyperaroused) or to shut down (hypoaroused). Many things can shrink our window of tolerance, including:

- Adverse childhood experiences

- Trauma later in life

- Chronic stress

- Lack of meaningful self-care (for example, not getting enough sleep or downtime, not caring for our bodies with enjoyable movement and nourishing food).

When we have a narrow window of tolerance, we are not resilient.

This infographic illustrates the concept nicely. If you’re reading this and thinking, “Ummm…my window of tolerance is whisper thin” and you have a history adverse childhood experiences (learn more about ACEs and take an ACE quiz through this excellent NPR article) or significant trauma, you may benefit from working with a mental health provider who specializes in trauma.

How does self-compassion help?

First, let me briefly explain what self-compassion is. First, it’s not self-esteem. Self-compassion is something you can cultivate, and it’s a combination of:

- Self-kindness: being warm and understanding toward ourselves when we suffer, fail, or feel inadequate, rather than ignoring our pain or beating ourselves up.

- Common humanity: recognizing that suffering and feeling inadequate are part of the shared human experience. These are things we all go through, not something that happens to you alone.

- Mindfulness: observing thoughts and feelings as they are, without trying to suppress or deny them. Combined with common humanity, this helps us put our troubles in perspective, neither dismissing them or making them feel bigger than they really are. It helps us stay balanced.

The opposite of self-compassion would be:

- Self-judgment: Getting angry and frustrated at ourselves when we make a mistake or our life isn’t what we feel it should be.

- Self-isolation: Feeling that you are the only one who makes mistakes or who has life disappointments. You become an island that no one can reach.

- Over-identification: Treating your unpleasant thoughts (which are really just words) and uncomfortable emotions (which will pass with time, like an ocean wave), as concrete reality, and getting caught up and swept away by our negative reactions.

Independent of its benefits for increasing resilience, practicing self-compassion can help us be healthier.

Exercise: Taking in the good

This exercise is adapted from the book “Hardwiring Happiness” by Rick Hanson. This exercise isn’t about building self-compassion, per se, but it does involve mindfulness.

- Pause for a moment and notice any experience of kindness, gratitude, or awe that you have experienced today or remember from the past. Maybe your neighbor drove you to and from work for three days while your car was in the shop, or you saw a blue heron rise up from a pond at dusk.

- Attune to the felt sense of the goodness of this moment — a warmth in your body, a lightness in your heart, a little recognition of “Wow, this is terrific!”

- Focus your awareness on this felt sense of goodness for 10–30 seconds. Savor it slowly, allowing your brain the time it needs to really register the experience and store it in long-term memory.

- Set the intention to evoke this memory five more times today. This repeats the neural firing in your brain, recording the memory so you can recollect it later, making it a resource for your own sense of emotional well-being, and thus strengthening the inner secure base of resilience.

- As you experience and re-experience the moment, register that not only are you doing this, you are learning how to do this. You are becoming competent at creating new neural circuitry for resilience.

Exercise: Self-compassion break

This exercise helps you shift your awareness to the present moment (aka mindfulness) and accept the moment for what it is (reducing struggling and denial, and therefore reducing suffering). It helps to practice this self-compassion break when your distressing emotions are still reasonably manageable, because jumping right in when thing feel really, really tough is challenging. Practicing when things are “less tough” will help you build skills you can use when things are “really tough.”

- When you notice a surge of a difficult emotion — boredom, frustration, sadness, shame — pause and recognize that you are suffering. This is mindfulness. Acknowledge it to yourself by saying, “This is upsetting” or “This is hard!” or “This is scary!” or “This is painful” or “Ouch! That comment hurt” or something similar.

- Put your hand over your heart. This activates the release of oxytocin, a hormone associated with feeling of love and well-being. Remind yourself that you are not alone, that other people have felt the way you do, and that we all suffer in our lives. This is common humanity.

- Ask yourself how you can express self-kindness in that moment. This can interrupt the auto-pilot tendencies of our less-helpful survival responses, which are driven by negative thought loops. One of these phrases may be helpful:

- May I give myself the compassion that I need

- May I learn to accept myself as I am

- May I forgive myself

- May I be strong.

- May I be patient

- Repeat these phrases to yourself (or some variation of words that work better for you). Continue repeating them until you can feel the internal shift: The compassion and kindness and care for yourself becoming stronger than the original negative emotion.

Acceptance of unpleasant situations or emotions can feel hard, and may seem strange (“Why should I accept something I don’t like?”), but accepting that something is what it is in that moment is a necessary the first step to identifying and taking wise actions to cope (if something is unchangeable) or to work towards a solution (if something can be changed). Similarly, when you accept yourself exactly as you are, rather than engaging in self-judgment and self-isolation, that opens the door to change. You are equally as deserving of your own compassion as others are.

Additional Resources

If this is an area you would like to explore, I recommend these books:

- “Resilient: How to Grow an Unshakeable Core of Calm, Strength and Happiness” by Rick Hanson

- “Hardwiring Happiness: The New Brain Science of Contentment, Calm and Confidence” by Rick Hanson

- “The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion” by Christopher Germer

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Disclaimer: All information provided here is of a general nature and is furnished only for educational purposes. This information is not to be taken as medical or other health advice pertaining to an individual’s specific health or medical condition. You agree that the use of this information is at your own risk.

Hi, I’m Carrie Dennett, MPH, RDN, a weight-inclusive registered dietitian, nutrition therapist and body image counselor. I offer compassionate, individualized care for adults of all ages, shapes, sizes and genders who want to break free from eating disorders, disordered eating or chronic dieting. If you need to learn how to manage IBS symptoms with food, or improve your nutrition and lifestyle habits to help manage a current health concern or simply support your overall health and well-being, I help people with that, too.

Need 1-on-1 help for your nutrition, eating, or body image concerns? Schedule a free 20-minute Discovery Call to talk about how I can help you and explore if we’re a good fit! I’m in-network with Regence BCBS, FirstChoice Health and Providence Health Plan, and can bill Blue Cross and/or Blue Shield insurances in many states. If I don’t take your insurance, I can help you seek reimbursement on your own. To learn more, explore my insurance and services areas page.

Print This Post

Print This Post